New York, 1895

New York, 1895

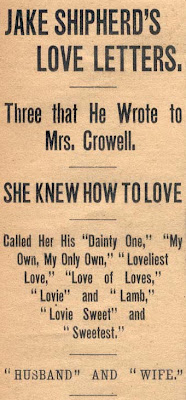

Three that He Wrote to Mrs. Crowell.

SHE KNEW HOW TO LOVE

Called Her His "Dainty One," "My Own, My Only Own," "Loveliest Love," "Love of Loves," "Lovie" and "Lamb," "Lovie Sweet" and "Sweetest."

"HUSBAND" AND "WIFE."

THE FARMER gave last week but an outline of one or two letters written by Jacob Rudd Shipherd of Richmond Hill to Mrs. Lydia S. Crowell. We lay before the reading public to-day three of Shipherd's letters to Mrs. Crowell, taken from full stenographic notes of the trial of the divorce suit. In one or two particulars these letters may seem offensive, but we have no right to mutilate them, as they are part of the court record; and if mutilated Shipherd might claim that the omission did him an injustice, so they are printed verbatim. The letters are but three out of a lot. Some of the statements in them may not seem entirely clear in the absence of Mrs. Crowell's letters to which reference is had. It seems that they posed as husband and wife. Mrs. Crowell's terms of endearment for Shipherd must have been extravagant and ravishing, but they can only be guessed at. Shipherd's terms of endearment are soul stirring and heart crushing. She was his Rock and his rest in her was better than ten millions of money could make it. She was his "My Dainty One," his "My Own, All My Own, My Only Own," "My Lamb," "Lovie Sweet," "My Love," "Sweetest," "Sweetest, Loveliest Love," and "Best Loved," "Lovie," "Dearest Dearest," "My Love of Loves," and so on.

As Crowell still has a suit pending against Shipherd for damages for the loss of Mrs. Crowell's affections, the letters will prove important evidence for Mr. Crowell.

The letters follow:

"The happiest woman in this world." "The happiest woman in this world." My my though, wouldn't that be almost too happy, dearie? She doesn't say she is that — she only says she would be that if. If — that is, she thinks she wd be that — if. If — well, that's lovely reading anyway. It sort o' warms m' heart & things. I think it brings a shine into m' eyes. I know it makes me glad like solid gold.

I went to the university at 4.30 & got back 2 hours later. Then I went to the Cong. Ch. to Chr. Endeavor. The minister was there & made me talk again, & after the preaching he & I talked some more, & some more brethren came up to introduce themselves & hope I would keep coming right along. One of them saw me there once in May & had remembered it ever since. Pa makes nice boys & girls, dont he, dear? After church Pa sent me to studying on 271 & remarked that if it was his wife & sister he'd left in Phila he sh'd go round and see if there weren't some letters. Nuff ced. I went, and there they were — 2 letters & a big pkg. There is a bright electric light within 10 feet of 271, & a broad stand-up desk to lean on. It only took 1½ minutes to absorb both letters, & 2⅛ seconds more to get into the box.

O my lamb! It was lovely of you — but this Pig had other views. He wanted her to buy her a syringe or some such thing for herself out of those virgin bills — it adds inches to the feel of his ears to have her little savings lavished on him this way. Now if I send her $2 special will she please got her a syringe for me — just for me, lovie sweet? Tell me true & nice my dainty one.

It makes me glad without surprise that you like the city of your kin. It is the smoothest, most restful and peaceable settlement of size I was ever in. I was sure you must like it — but left you free to find your own impressions. Mayhap you & I will settle there or near there yet & put on (both of us) the plain dress and say "thee" and "thine" and so drift out together upon the sleeping sea. Would my love like it?

Every word you write sets my heart a-glow, sweetest. And the full, clear name at the end shines like a star cluster in my eyes. My own, my own, my only own — and all my own.

Your No. 6 gladdens me this morning — but, O my loveliest love, every day I find your words talking for me better than my own. When I was coming away and you were rebelling — not naughtily, only helplessly — and I tried to comfort you with some reminder about letters, & you retorted indignantly, "A piece of paper instead of my husband. No, I want my husband." I thought at first — just for an instant — that you were scarcely appreciating letters.

A great many times since those words have come back to me, and I have found my respect for them steadily increasing, and this morning, after opening your parcel with quivering eagerness & feasting upon every mark of your pen, I lay it down as one famishing with thirst might set down the empty cup in the bottom of which he had found a few trickling drops only, & my soul cries out "And is that all? How am I to live all day on that? and probably must live 24 hours on it? And then there will be only as much more. O this is sheer starvation; and are there weeks and weeks of it yet to come?"

And then like a flash from heaven came back your words to me "A piece of paper instead of my husband. No, I want my husband." And all my soul cried out "Those words are true." The words above all others in this No. 6 that my soul responds to this morning are these: "When I am with my husband I feel as if I would like to shut out the world and be alone with my dearest, dearest."

The greater facts of life are the same, regardless of all time & space & surroundings. To each other we are alone — always, everywhere — what is ours is as separately ours as if God and we alone were alive. If our holy of holies could be entered, there could be no sacredness assured to us. But only God has access there, and he comes in only to cheer and bless and enrich and approve.

The longing we both feel to be absolutely (for the most part) left to ourselves, is only the nimbus of the sun of our joy — a halo surrounding the pure & central shining. It is sweet to be quite by ourselves — alone, alone, alone, alone, in every sense and manner of form. It is pain, a weight, a clog, a stricture, when we are parted in any manner, when any conditions intervene to divide us in any way to any extent. But it is not immeasurable relief to remember that as matter of fact, the most holy place which is ours alone can never be entered by any profane foot or eye or car. That what is truly ours alone can never be shared under any conceivable conditions by any other than our Father alone? And that all these interrupting experiences are in their very nature transient and fleeting — a part of those "light afflictions which are but for a moment."

Were it not so, O best loved, it seems to me I could not endure to live. You have had some hints — the merest hints only — of what I suffered when an infinitely lesser love was — in a manner, profaned and outraged. I had not then learned of the Inner temple of ALL; I did not then know where to take refuge. There are no words to tell of the uplifting of joy I have since known nor of the horrors of darkness out of which I have since been saved. Now love me somewhat as I do not mean less; I only mean that for the first time in my life I seem to have met one who can love as I can love.

Always hitherto I have given dollars for pennies, diamonds for stones — I mean of course outside my own family. Always hitherto, for one reason or another I have been compelled, even inside my own family, to limit my loving, to restrain myself, to forbid myself, to repeat over and over every hour of the day — "Stop here, stop here, stop here." Sometimes I have wondered how God could compel me to desire so much and to forbid myself almost all of it. But never mind now. In you & through you God has shown me so much of present sweetness, such promise of future sufficiency, and such eternal certainty — that I can now wait with such hope and such measure of content as I never knew before I knew you.

We are saved easily by hope, when our hope rises out of sufficient knowledge. Hope that is blind is but another form of desperation. Faith that does rise out of knowledge is but a dream and a snare.

I am glad Father cares. It would be much more agreeable to me to alternate the formal address; I know mother cared, and was not sure that Father did. I have obtruded so much loving upon so many people that I am very timid now. There is a sense in which it is necessary to be "weaned," nor is the experience seriously painful when the conditions are normal; but in the sense in which you cry out, "I shall never be weaned, darling, never," all my soul cries with you. Not only will it never be easier to be torn from you — it must always be harder and harder.

But we may learn & shall learn now (largely) to ignore the conditions of time and space. But for this our whole life wd grow harder & sorer, & wd soon become intolerable. Yes, lovie; please send me one of the photos. I must begin my day's work now.

This will be due in N. Y. at 1 P. M. tomorrow — in good season for R. H. on Monday A. M. O my love of loves.

At the office I found 4 letters waiting for me — four. I had them all for breakfast, and now I sit before my wife's No. 9, No. 10, No. 11 with a sense of wealth unknown before. I will write to Julia to hand you the $2. Let me know that you get it. I could write you pages of history about my care of your husband. If he gets any harm while in my charge it will not be my fault — the first cold night for example, the cold was so unexpected that no one was ready. The next morning at breakfast every one was clamoring about the inability to keep warm. But I wasn't caught napping, & I took care of your husband. I made him report to me every two or three minutes when he was awake. Of course we started with the foot muff. Then came the b-quilt. Next the knee quilt. Then a thin under vest; then thick drawers. Then thin stockings. Then woolen stockings over them. There were a heavy pair of new & handsome blankets & coverlid all the time, but as the night wore on & the cold steadily strengthened I found the man was still a shade too cool, & I bounded out once more. I brought him his brown coat and made him sit up & put it on. He laughed a pile & declared that in all his life he had never worn a coat in this way, but of course I was inexorable; it is easy enough to be flinty when you have a duty to do. His wife was right before me every minute, & I was hard as granite in her presence. There is nothing in the universe (I suppose) so flinty as pure love.

Julia writes that you mentioned the flowers I sent her but gave her none; I don't understand it; As to Sadie I think you are wise to be silent & let things take their course — no effort of ours can change anything and certainly we have no wisdom as to the future. How can we tell whether it is best, she sh'd. go with us or not? And is it not certain that only the best things will be given us? Is not the best good enough?

I have myself thought about a thicker overcoat. It is to say whether it will be needed or not. If I send for it, please pack it in one of those boxes you will find in the storeroom closet: "To whom does that table belong?" What table, dear. "I took charge of the small envelope." Thanks dearie. "Did your umbrella go all the way to Atlanta with you?" I am able to assure you, dear, upon the highest authority that my umbrella did go all the way to Atlanta with me. If you will be good enough to step into my room for a moment I will show you where it stands this moment, just over there in the southwest corner of my room, beside my cane. "Cane?"

Sure enough, your spouse hadn't told you, had he? Well, forgive him, and let me tell you all about it; He moves around more or less evenings, always to the P. O. and 2 or 3 times a week to some public place & felt sort o' unprotected in the dark, besides, he is so clumsy he likes to have something to sound the darker places with, and I told him to go right off and get him a cane, that his wife wouldn't allow the question to be debated, etc. He only hesitated about the expense but when I quoted his wife he knew I was right and said no more. He chose a very substantial hickory stick, closely like one he carries at home, with a round handle. It is handsome and it is strong, and he never goes out in the dark without it. It cost 75 cents & wd. be cheap at twice the money. His father said he'd provide the money (I hear his father is quite well to do; at least in comfortable circumstances.)

"I will have to come back to the thought that everything is right." I wouldn't love if I could do better. I think we have the right to demand always the best; for myself I confess I never came to that thought till I was forced to it by the failure of every other refuge; then I got away from it again directly, and I have got away from it a million times since and I never get back to it till I am driven back to it. Never.

This is the reason I do often hear these lines, "Blest be the tempest, kind the storm that drives me nearer home."

"I hope Pa will solve the lawyer problems and then your mind will rest." No dearest, not then. First because I can't wait. "I want it now." I must have it now. I can't stand on any uncertainty any more. Since I have once stood on the Rock.

Second, because I couldn't rest on any human thing — not for a moment. If I had the new charter now I could not rest on it an instant. If I had ten millions of money besides I couldn't rest on both of them a instant: Since I have found the Rock. Since I have found the Rock I can never rest anywhere else. I do rest now darling, absolutely, utterly.

There are no longer any problems (in the sense) for me. All my problems are solved. "Thy Maker is thy husband." Multiply your rest in your husband by a thousand millions or so — that is what it is to rest in Him. "Will you accept an unlimited number of kisses?" Try me, love. Try me.

————————

When Jacob Rudd Shipherd was first accused of wrongfully detaining Miss Bennett, and when he was strongly suspected of the infamy which was developed in the Crowell divorce trial, the Jamaica Standard's columns were used in his defense. It is said now that money was paid for the use of the paper.

—The Long Island Farmer, Jamaica, NY, June 21, 1895, p. 1.

No comments:

Post a Comment